~ 9 min read

Breaking Bubbles: Art and Science in a Fractured World

In an age where trust in science, facts, and authority is rapidly eroding, art may offer a surprising way forward. While science seeks clarity and truth, art embraces ambiguity, interpretation, and emotion—qualities that can foster deeper engagement with the world. Historically, art and science were seen as opposites, yet both rely on observation and curiosity. Can art help restore trust by offering new ways of seeing and understanding? This piece explores the intersection of art and science, questioning whether creative expression can bridge the growing divide in a world overwhelmed by misinformation and ideological bubbles.

Trust worldwide is on the verge of breakdown. Can we trust authorities? Can we trust science? Can we trust facts? Lies, conspiracy theories and fabrications reach all corners of the world and spread quicker than the COVID-19 virus did. This undercurrent of falsehoods threatens to erode communities, societies and even the international order. It feels like a unique phenomenon, but our parents and grandparents have been here before (of course!). People have aways tended to live in bubbles, long before we started to use that word as a metaphor for an isolated sphere of ideas and like-mindedness. Religion, ideology and conspiracy theories are of all times and have always become attractive during periods of significant life-threatening stress. This time science - again - has not been able to restore the balance. But could art be of any help?

During the late 19th and a large part of the 20th century, the worlds of art and science were disconnected. The emotional world of the heart and the rational world of the mind were seen as opposites and disjuncts. Indeed, for academics, policy makers and the public at large, science was held to be exact, rule-bound, descriptive and objective. The arts on the other hand, were seen as emotional, creative, subjective and fuzzy. Of course, there are important distinctions: works of art are often intended to be ambiguous – there is no greater joy than asking spectators what they think that the meaning of an artwork is and then to discover the variety of viewpoints that also include perspectives that never were in the conscious mind of the creator. In contrast, science is expected to be unambiguous and rigorously ‘true’ to the data.

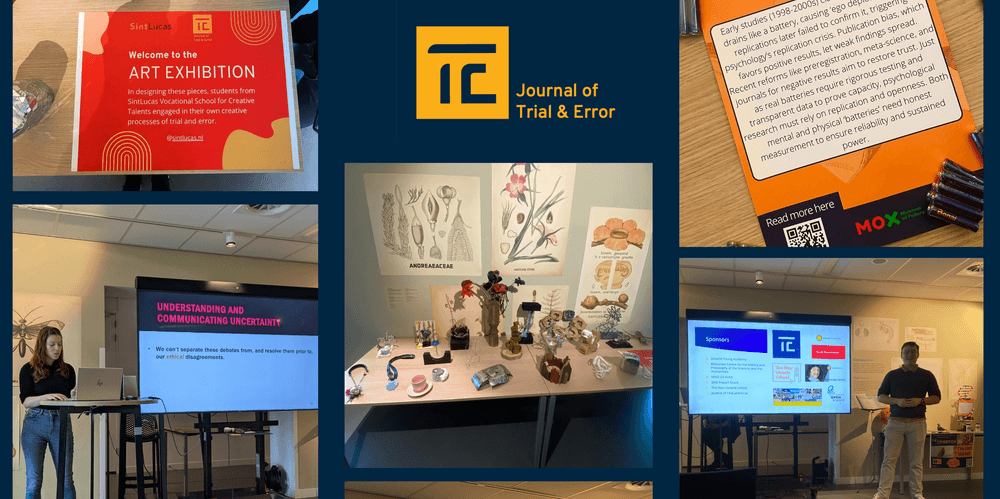

Recently we seem to be returning to an approach more like that of the 18th century and earlier periods, when great scientists might also be gifted painters or composers, such as Samuel Morse, a gifted portrait painter and the inventor of the telegraph. Artists deployed research and new discoveries in their work such as Rembrandt's ‘Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes', or the arrival of steam in Monet’s ‘Gare Saint-Lazare’. The renaissance man par excellence is of course Leonardo da Vinci. Initiatives such as ‘I art my science’ or the exhibition Observations provide examples of how art and science relate and can reinforce one another.

What both worlds have in common is ‘observation’: a fervent commitment to observing, interpreting and representing the world. I believe that the most important contribution from the arts is that it allows for a different way of experiencing how we observe, that different – and often unforeseen - perspective exists and also that the purposeful intention of an artwork can be overtaken by new realities. One of my lithographs, originally meant to illustrate the disconnect imposed by economic sanctions (and later used as a book cover), seamlessly fit into the Broken links exhibition during the COVID-19 pandemic.

(HOW) COULD ART BE PART OF A SOLUTION?

Art itself has been often under attack for being seen as part of an ideology. It is telling that in Orwell’s 1984 the ‘Ministry of Truth’ has a special attention for the fine arts. Art has indeed been a tool for the powerful from the Egyptian pharaohs to Chinese Maoism and this recognition is one of the driving forces of the movement towards decolonization of the arts. So, art is certainly not a panacea, but art certainly has something to offer to science.

For one thing, art has the ability to help people remember facts and inconvenient truths. Memorials for the COVID-19 pandemic are one example. Although it can be challenging to create a memorial when the ‘enemy’ is invisible, and the victims dispersed and anonymous, they can still become an important part of collective memory. Spontaneous, informal monuments have popped up, such as the wall of hearts along the Thames, overlooking Parliament, where for every COVID-19 victim family members and volunteers could paint a heart with their name on it.

There are more examples of such monuments in our culture. For instance, various altarpieces and depictions of saints were created in response to the bubonic plague, a disabled water pump on Broad Street in London was erected to commemorate the cholera outbreak caused by contaminated water, and in Amsterdam a structure incorporating an abacus - the HIV/AIDS monument by Jean-Michel Othoniel - has become a spot for regular commemoration meetings. They show that art can carry a message over many generations.

I see two contributions that would seem to fit into the curriculum of most scientific curricula. First is the art of interpretation. Works of art do not only require a creator but also an audience and while the creator may have a clear message in mind with her artwork, the audience may see other things. It is a very useful, sometimes sobering but always joyful experience to learn that others do not see what one intended to show. An art class may provide that lesson in a less stressful and more open way to students.

Second is the art of observation. Many sciences train observation specific to the field of enquiry and often relying on machines or instruments. This makes sense when the observations cannot be done with human senses, but typically even those working with nano or cosmos level observations can learn from observation through human science. Art offers a multidimensional and truly multidisciplinary experience.

ARTFUL OBSERVATION AND SCIENCE

Observation1, in the words of the Vietnamese activist artist Tu Anh Hoang is a fundamental aspect of human experience. It involves more than just seeing; it is an active process of engagement of the self with the world, allowing for deeper understanding and insight. The British geographer, painter and community artist Imogen Bellwood-Howard sees art and science as forms of analysis. Analysis of what takes place in Euclidean space and of social processes and phenomena. The precursor to this analysis is observation, and interpretation of these observations.

The Dutch social scientist and novelist Ruben Gowricharn points out that differences in perception and interpretations have consequences, not only for the political debate but also for science. In the exact sciences and life sciences, you can report an observation of, for example, the behaviour of molecules, without being disputed by the object. In the humanities, however, the observer risks that his report may not go down well with the group being studied.

Political scientist Helen Hintjens writes that observation grounds you in reality. Attentiveness is rooted in observation. Observation in art is not limited to perceiving your subject, but also the observation of your own soul and mind. And beyond that, the soul and mind of others. For example, if you are a writer, you are concerned with the soul and mind of the future viewer of your work (unless it never leaves your studio).

Observations are not only rational; emotions are an important part of them. As Maartje Raijmakers explains: ‘An observation grabs my attention and makes me search for what I am actually looking at, and what experiences it evokes in me'. Sometimes observations can be imagined: Vincent Icke, an astrophysicist and visual artist investigates how aliens would see space. In his artworks he investigates how the human eye has difficulty with different shades of blue, and he developed installations that allow visitors to experience fundamental physics principles.

My own work as a professor and lithographer allows an important role for uncertainty, chance, errors, mistakes and serendipity to play in both formal research strategies and in the strictly prescribed chemical procedures of lithography. Observation is key in this process, as accidental discovery brings gifts as well as risks that emerge both at the macrolevel (the composition or the image as a total), its components (the colour separations and structures), and the details. Since variation occurs at all these levels, and because lithography is a natural process, you need to be constantly alert, not only rely on your eyes. In a lithographic atelier you also need to smell and feel and be aware of temperature and humidity. Even air pressure adds to the physical challenges of operating heavy stones and a press that was constructed around the time Edison invented the light bulb. If you miss the signals on either the stones or on paper (both can behave quite differently) you can end up with distortions and messy, unsharp and weak prints. Not useless, because you will have learned a lot, but certainly not stuff that you can show or sell. Creating a role for chance implies that you will not know what the exact result will be (this is in my experience ‘luck’) but your approach is professional as it creates the right conditions for new and interesting findings. Many presented results are part of the art of economic science but more importantly is that we all know about the graveyard where we burry our non-publishable results. The same is true in a lithographic atelier, when the printer’s secret reigns. Seeing in these contexts requires trained observation and a mind open to finding the opposite of what you expect.

Ultimately, the true power of art lies not in providing answers, but in challenging us to look closer, think deeper, and engage with the world—and each other—with renewed curiosity and openness. By embracing the art of observation, we may find unexpected connections between disciplines, allowing both science and art to contribute to a richer, more nuanced perception of truth. This is an asset in a world where trust in science and facts are increasingly under siege: art offers a unique way of seeing, feeling, and questioning—one that can complement scientific inquiry and open new avenues for understanding.