~ 12 min read

DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.36850/kr5s-q873

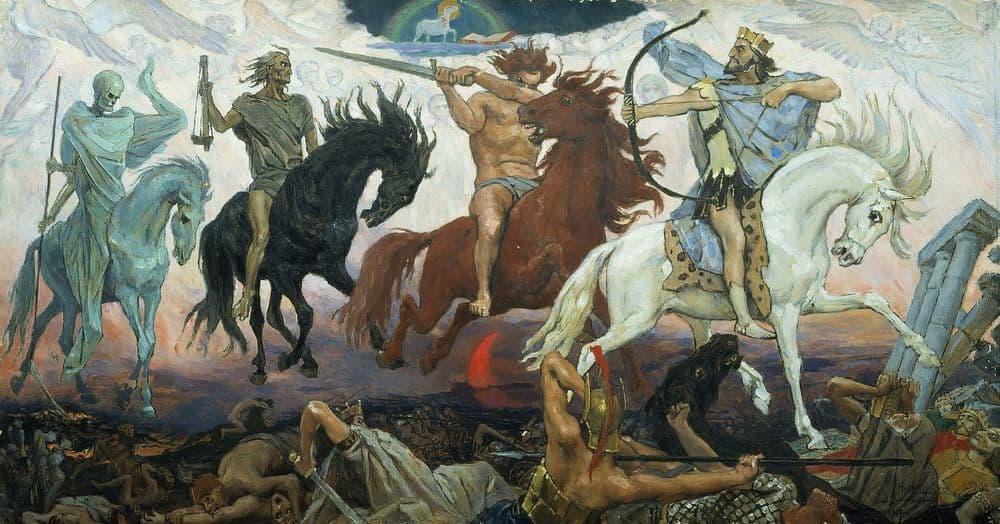

The Four Horsemen of the Crisis in Psychological Science

Psychological science is in a crisis. It’s been in a crisis for quite some time. For anyone doing research in psychology, or just paying attention to the field, this should come as no surprise. The most common statistical framework we use has been criticized since its inception (e.g., [1] , [2] , and [3]), many famous findings in psychology fail to replicate [4] [see 5 and 6 , for two examples], and much of the publication process incentivizes researchers to engage in questionable research practices (e.g., p-hacking, RUSS, HARKING, and so on) [7].

Like I said though, this is old news. Scientists have known about these problems for decades, yet improvements are slow to come, if they’re coming at all [8]. While issues of statistical inadequacy, replication failure, and poor methodology have dominated most of the discussion about methods reform in psychology, other important problems in psychological research have surfaced in its wake. In this post, I want to briefly introduce three lesser-discussed crises in psychological research that, along with the replication crisis, form what I call the four horsemen of psychological science. The goal of this post is chiefly to raise awareness of these issues and present them in a simple and condensed fashion. It is also to discuss how JOTE may act to help curtail some of these crises, a point which I raise at the end of the post.

White Horse: The Replication Crisis

The replication crisis is perhaps the best known crisis in psychology and science more broadly [9]. It has already been given much more detailed explanations than I can give here (see [10] for a review and assessment), so I will just summarize. Put succinctly, the replication crisis in psychology revolves around the fact that when findings are shown to be statistically significant in one study, they fail to be statistically significant in other studies that follow the same research protocol. This is an important problem for psychology, with an estimated two-thirds of studies failing to replicate [10]. The reasons for these failures are manifold, from institutional pressures to publish positive findings [11] to a misunderstanding and misapplication of statistics and statistical power [12].

Though it gets the most press, the replication crisis is neither the sole nor most widespread issue in psychology. While replication is a problem to be sure, it alone is more akin to a symptom of a broader disease than it is to an open stab wound.

Red Horse: The Measurement Crisis

To illustrate this last point, imagine we have a finding that perfectly replicates. That is, if the proposed research protocol is followed correctly, we will always find a statistically significant difference between measured scores on the dependent variable (DV) in one group vs. measured score on the DV in the other group (groups here representing levels of the independent variable; IV). If the replication crisis were the only thing psychological science had to contend with, all would be well here.

Unfortunately, there is more than replication to worry about in psychological research. As Flake & Fried [13 & 14 ] point out, when we replicate a finding, we assume that the construct underlying that finding was properly measured to begin with. For example, if we demonstrate that social rejection increases negative emotional state, we first have to assume that we can meaningfully measure and quantify (a) social rejection and (b) negative emotional state. However, as the authors demonstrate, researchers rarely give good reason to make such an assumption. Instead, researchers often engage in what Flake and Fried call “questionable measurement practices”, where they hide (or perhaps do not even question) the process by which their measures are chosen and their constructs are defined. Oftentimes, new measures are invented for the purposes of a single study, seemingly out of the blue, with little justification as to why this measure would be chosen over a previously established one. Even when a rationale is provided for these choices, measures are seldom rigorously validated and, when they’re purported to be, and appropriate statistics are sparsely reported [14] .

This so-called “measurement schmeasurement” attitude is a problem, because it means that even if a finding is replicable, we are still not sure exactly what is being replicated. It is for this reason that replication does not stand alone as the only crisis in psychological research. Indeed, it may not even be the primary one! After all, it is not very useful to replicate a finding that we can’t properly explain to begin with.

Black Horse: The Generalizability Crisis

Now imagine we have a field of research that is both highly replicable and properly measured. That is, we have a valid and reliable way of measuring our DV and IV and we can consistently demonstrate that the IV exerts a statistically significant effect on the DV across a variety of studies. Again, at first glance, it seems as though things are in good shape.

Enter the issue of generalizability. While it is important to combat both questionable research and measurement practices in experimental psychology, from the perspective of generalizability, these efforts are somewhat misguided [15] . Rather, the key issue researchers ought to focus on is to what degree their results match up with what they are supposed to predict in the real-world. To take our example from above, say that we choose valid and reliable measures of social rejection and emotionality and, using these measures, find a replicable effect across studies. Despite our efforts, we are still likely only using a small number of operationalizations of social rejection and negative emotion. These measures do not, however capture the broad and diverse experiences of being rejected—from divorce to being “swiped left” on Tinder—nor does it fully provide an account of negative emotions—from devastation to minor discomfort (for a similar argument by a leading figure in the field from which this example is taken, see [16] ). This remains the case even when results are replicable across many research contexts (so-called “conceptual replication”), because we are still talking about a narrow conceptualization of a psychological phenomenon that has no guarantee to apply to the myriad of real-world manifestations of said phenomenon. Furthermore, even when measures are properly validated, such that we can have strong confidence we are truly measuring negative emotion, psychological experiments can make few claims about how these emotions are experienced and elicited outside the lab and whether results extend to those situations. As Yarkoni [15] puts it: “The root problem is that when the manifestation of a phenomenon is highly variable across potential measurement contexts, it simply does not matter very much whether any single realization is replicable or not.” (p. 13).

Pale Horse: The Practicality Crisis

Finally, imagine we now have a research field that replicates, is validly measured, and generalizes to real-world phenomena. This is to say that we find some IV and DV relationship across a series of independent studies, we are confident our measurements properly capture the construct, and this relationship generalizes to a variety of real-world manifestations. Surely in this case our results are safeguarded from psychology’s crises?

Unfortunately not. Even if our results meet the criteria mentioned above, we have so far neglected a central question when doing research: “Who cares?” And when it comes to psychological research, the answer seems too often to be “no one much”. Berkman and Wilson [17] make this point more formally. They argue that, as a field, much of academic psychology has lost its sense of practicality. Theories in psychology live and die without much regard for how they could be applied to help improve society in a meaningful way. As a key point, the authors highlight the artificial distinction that’s been set up between “basic” and “applied” research. Underlying this distinction is the (incorrect) belief that “basic” research applies to some universal human figure, whereas applied research focuses on the specifics of a situation or group. However, for reasons we grappled with in the previous section, no research can in reality test such universal claims. All experimental samples are constrained by their components (the participants) and their contexts (the fact that they are experiments to begin with). In practice, these components are even more limited to WEIRD participants and contexts (Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic) [18] . As such, the authors make the case that we should abandon this distinction and focus on researching topics that are of general interest to a group or society in order to produce work that stands to benefit that community.

From this perspective, our results may very well be valid, replicable, and generalisable, but to what end? If these results are born and die in the “ivory tower”, never to affect change in society, be applied by policy-makers, and ultimately help people, then what good do they serve?

Avoiding Apocalypse

Faced with these four horsemen, we might ask whether our sins have finally caught up with us; whether now the only options are to run to the hills or to brace for the oncoming stampede. I argue, instead, that now is the time for self-reflection and transcendence. When the replication crisis first hit, many scientists recognized that things needed to change. However, not much did. Perhaps this lack of change was due to the fact that, in many respects, the replication crisis was not an existential threat to psychological research. After all, the solution to the crisis was simple, albeit challenging: acquire more powerful samples, stop questionable research practices, gain a better understanding of statistics, promote transparency, and encourage replication [e.g., 19 ]. It’s business as usual, just a little different.

However, the crises I have outlined here—measurement, generalizability, and practicality—are not so easily dealt with. They require a fundamentally different outlook for how we conceptualise psychological science and its position within academia and society in general. Not only do these crises demand that the difficult methodological changes needed to ensure proper replication be in place, but they also require us, as scientists and consumers of science, to reflect upon what it is we value in psychology. Indeed, they require us to be philosophers as well as scientists.

It is for this reason I see JOTE as a step forward in combating the crises I have discussed in this post. While JOTE addresses the basic requirements of methods reform—publishing of null results, support of replication work, Open Science, and so on— it goes much further. It also opens a dialogue with thinkers from other fields who can contextualise the research that gets published. Commentators from sociology, philosophy, and anthropology are encouraged to discuss whether the research published in JOTE uses appropriate measures; whether it ought to bear any weight in broader discussions surrounding a phenomenon; and whether it is ultimately useful for society.

Certainly, JOTE alone cannot solve all the crises that I have outlined here. As I mentioned, doing so requires fundamentally rethinking how we conduct science. While I have focused on psychological science in this post, it is likely similar crises are ready to break in other fields of science, if they have not already. I believe that by uniting the scientific community and the humanities, JOTE is uniquely positioned to tackle these crises in a novel and necessary way that researchers from all areas could benefit from. Whether this approach works to curb the many worrying trends constantly bubbling up in psychological science and beyond remains to be seen. However, I argue that if any approach can begin the hard work of figuring out what it is we are all really doing when we engage in scientific research, it is one like JOTE’s, that unites thinkers across many field in transcending our limitations and collectively searching for truth in science.

References

[1]: Boring, E. G. (1919). Mathematical vs. scientific importance. Psychological Bulletin, 16, 335–338. doi:10.1037/h0074554

[2]: Berkson, J. (1942). Tests of significance considered as evidence. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 37, 325–335. doi:10.1080/01621459.1942.10501760

[3]: Rozeboom, W. W. (1960). The fallacy of the null hypothesis significance test. Psychological Bulletin, 57, 416–428. doi:10.1037/h0042040

[4]: Pashler, H., & Wagenmakers, E. J. (2012). Editors’ introduction to the special section on replicability in psychological science: A crisis of confidence? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7(6), 528-530. doi: 10.1177/1745691612465253

[5]: Hagger, M. S., Chatzisarantis, N. L. D., et al. (2016). A Multilab Preregistered Replication of the Ego-Depletion Effect. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11(4), 546–573. doi: doi.org/10.1177/1745691616652873

[6]: Klein, R.A., et al. (2019). Many Labs 4: Failure to Replicate Mortality Salience Effect With and Without Original Author Involvement. Retrieved from: https://psyarxiv.com/vef2c

[7]: John, L. K., Loewenstein, G., & Prelec, D. (2012). Measuring the prevalence of questionable research practices with incentives for truth telling. Psychological science, 23(5), 524-532. doi: 10.1177/0956797611430953

[8]: Replication Index (February 20, 2020). The Lost Decades in Psychological Science. Retrieved from: https://replicationindex.com/2020/02/20/the-lost-decades-in-psychological-science/

[9]: Ioannidis, J. P. (2005). Why most published research findings are false. PLos med, 2(8), e124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124

[10]: Open Science Collaboration. (2015). Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science, 349(6251), aac4716. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4716

[11]: Lilienfeld, S. O. (2017). Psychology’s Replication Crisis and the Grant Culture: Righting the Ship. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(4), 660–664. doi: 10.1177/1745691616687745

[12]: Tressoldi, P. E. (2012). Replication unreliability in psychology: elusive phenomena or “elusive” statistical power? Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 218. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00218

[13]: Flake., J. & Fried, E. (2019). Measurement Schmeasurement: Questionable Measurement Practices and How to Avoid Them. Retrieved from: https://psyarxiv.com/hs7wm/

[14]: Flake, J. K., Pek, J., & Hehman, E. (2017). Construct Validation in Social and Personality Research: Current Practice and Recommendations. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8(4), 370–378. doi: 10.1177/1948550617693063

[15]: Yarkoni, T. (2020). The Generalizability Crisis. Retrieved from: https://psyarxiv.com/jqw35

[16]: Baumeister, R. (2020). Do Effect Sizes in Psychology Laboratory Experiments Mean Anything in Reality? Retrieved from: https://psyarxiv.com/mpw4t/

[17]: Berkman, E. & Wilson, S. (2020). So Useful As A Good Theory? The Practicality Crisis in Academic Psychology. Retrieved from: https://psyarxiv.com/h3nwd/

[18]: Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and brain sciences, 33(2-3), 61-83. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X0999152X

[19]: Kline, R. B. (2013). Beyond significance testing: Statistics reform in the behavioral sciences. American Psychological Association.